How to Deploy Machine Learning Models

A Guide

Introduction

The deployment of machine learning models is the process for making your models available in production environments, where they can provide predictions to other software systems. It is only once models are deployed to production that they start adding value, making deployment a crucial step. However, there is complexity in the deployment of machine learning models. This post aims to at the very least make you aware of where this complexity comes from, and I’m also hoping it will provide you with useful tools and heuristics to combat this complexity. If it’s code, step-by-step tutorials and example projects you are looking for, you might be interested in the Udemy Course Deployment of Machine Learning Models. This post is not aimed at beginners, but don’t worry. You should be able to follow along if you are prepared to follow the various links. Let’s dive in…

Contents

- Why are ML Systems Hard?

- ML System Architecture

- Key Principles For Designing Your ML System

- Reproducible Pipelines

- Tooling

- Testing

- Deployment and Scaling

- Monitoring and Alerting

- What others do

- The Changing Landscape

1. Why are ML Systems Hard?

Machine learning systems have all the challenges of traditional code, plus an additional set of machine learning-specific issues. This is well explained in the paper from Google “Hidden Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems”. Some of the key additional challenges include:

The need for reproducibility: Particularly in industries under the scrutiny of regulatory authorities, the ability to reproduce predictions made by models means that the quality of software logs, dependency management, versioning, data collection and feature engineering pipelines and many other areas has to be extremely high.

-

Entanglement: If we have an input feature which we change, then the importance, weights or use of the remaining features may all change as well (or not). This is also referred to as the “changing anything changes everything” issue, and means that machine learning systems must be designed so that feature engineering and selection changes are easily tracked.

-

Data Dependencies: In a ML System, you have two equally consequential components: code and data. However, some data inputs are unstable, perhaps changing over time. You need a way to understand and track these changes in order be able to fully understand your system.

-

Configuration: Especially when models are constantly iterated on and subtly changed, tracking config updates whilst maintaining config clarity and flexibility becomes an additional burden.

-

Data and Feature Preparation: If left unchecked, vast webs of of scripts, joins, scrapes and intermediate output files can form around various steps of data munging and feature engineering. Unpicking or maintaining such “glue code” is a deeply frustrating and error-prone task for even an experienced software developer.

-

Detecting Model Errors: There are plenty of things that can go wrong in machine learning applications that will not be picked up by traditional unit/integration tests. Deploying the wrong version of a model, forgetting a feature, and training on an outdated dataset are just a few examples.

-

Separation of Expertise: Machine learning systems require cooperation between multiple teams, which can result in no single team or person understanding how the overall system works, teams blaming each other for failures, and general inefficiencies.

ML Systems Span Many Teams (could also include data engineers, DBAs, analysts etc.):

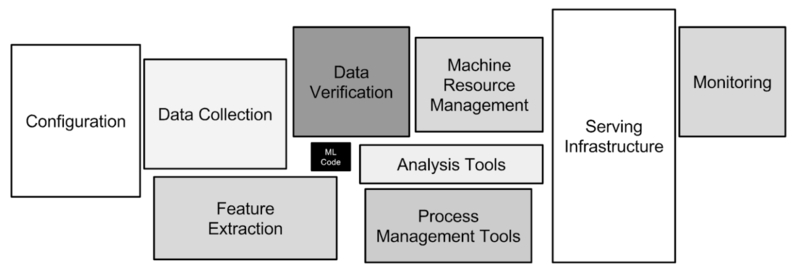

One of the reasons why the deployment of machine learning models is complex is because even the way the concept tends to be phrased is misleading. In truth, in a typical system for deploying machine learning models, the model part is a tiny component. This diagram from the above-mentioned paper is useful for demonstrating this point:

The model is a tiny fraction of an overall ML system (image taken from Sculley et al. 2015):

What this means is that you cannot think about model deployment in isolation, you need to plan it at a system level. The initial deployment is not really the hard part (although it can be challenging). It’s the ongoing system maintenance, the updates and experiments, the auditing and the monitoring that are where the real technical debt starts to build up. It is necessary to think carefully about your system architecture if you wish to meet the challenges outlined in this section.

2. Machine Learning System Architecture

The starting point for your architecture should always be your business requirements and wider company goals. You need to understand your constraints, what value you are creating and for whom, before you start Googling the latest tech. Questions of note might include some of the following:

- Do you need to be able to serve predictions in real time (and if so, do you mean like, within a dozen milliseconds or after a second or two), or will delivery of predictions 30 minutes or a day after the input data is received suffice?

- How often do you expect to update your models?

- What will the demand for predictions be (i.e. traffic)?

- What size of data are you dealing with?

- What sort(s) of algorithms do you expect to use (and do you really need them)

- Are you in a regulated environment where the ability to audit your system is important?

- Does your company have product-market fit? (i.e. do you need to prepare for the system’s original purpose to radically change)

- Can this task be done without ML?

- How large and experienced is your team - including data scientists, engineers and DevOps?

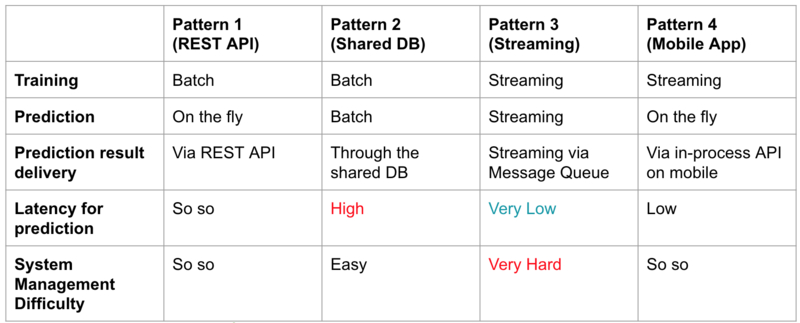

Once you’ve taken stock of your requirements, it’s useful to consider some of the high-level architecture options for a machine learning system. This is not an exhaustive list, but many systems do fall into one of the following buckets:

Four potential ML system architecture approaches:

Each of the above four options has its pros and cons, as summarized in the table. More granular details can vary significantly within these broad categories - for example each of these can be created with either a microservice architecture or a monolith (with all the usual tradeoffs that have been discussed ad nauseam). It is worth mentioning that option 3 tends to require a much more complex design and infrastructure setup. Typically such designs rely on a distributed streaming platform such as Apache Kafka. Pattern 1 tends to be the best trade-off in terms of performance vs. complexity, particularly for organizations without a mature DevOps team.

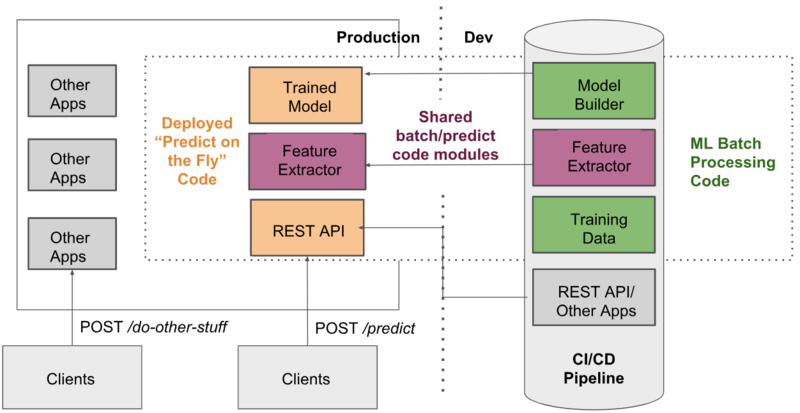

An example system diagram for a pattern 1 system:

Language Choice

It will make life easier if the language you use in your research environment matches your production environment. This typically means Python, due to its rich data science and data processing ecosystem. However, if speed is a real concern then Python may not be feasible (although there are many ways to get more out of Python). When to make the switch because of performance concerns is an important decision. This decision to switch language should only be made when necessary, as the additional communication overhead between research and production teams becomes a significant burden. Of course, if all your data scientists are fluent in Scala, this isn’t something you have to worry about.

3. Key Principles For Designing Your ML System

Regardless of how you decide to design your system, it is worth bearing in mind the following principles:

- Build for reproducibility from the start: Persist all model inputs and outputs, as well as all relevant metadata such as config, dependencies, geography, timezones and anything else you think you might need if you ever had to explain a prediction from the past. Pay attention to versioning, including of your training data.

- Treat your ML steps as part of your build: Which is to say, automate training and model publishing

- Plan for extensibility: If you are likely to be updating your models on a regular basis, you need to think carefully about how you will do this from the beginning.

- Modularity: To the largest extent possible, aim to reuse preprocessing and feature engineering code from the research environment in the production environment.

- Testing: Plan to spend significantly more time on testing your machine learning applications, because they require additional types of testing (more on this in part 6).

4. Reproducible Pipelines

As you shift from the Jupyter notebooks of the research environment to production-ready applications, a key area to consider is creating reproducible pipelines for your models. Within these pipelines, you want to encompass:

- Gathering data sources

- Data pre-processing

- Variable selection

- Model building

Naturally, this is easier said than done, particularly at the gathering data sources stage if your data is a moving target. If reproducibility is a regulatory requirement, you will need to think particularly carefully about things like controls and versioning on files, databases, S3 buckets and other data sources used during your model training. Your pipelines should allow you to lift and drop persisted, pre-trained models into other applications, where they can serve predictions. Whilst it is possible to write custom code to do this (and in complex cases, you may have no choice), where possible try and avoid re-inventing the wheel. A couple of nice solutions to consider are:

There are plenty of other options here - check the docs of your ML Framework of choice.

5. Tooling

Containers

Since the arrival of Docker in 2013, containerization has revolutionized the way software is deployed. The benefits of containerization apply equally if not more so for machine learning systems. Reproducing containerized systems is much easier because the container images ensure operating system and runtime dependencies stay fixed. The ability to consistently and quickly generate precise environments is a huge advantage for reproducibility during testing and training. Containerization also works well with modern CI/CD workflows, and has implications for scaling which I’ll talk about more in part 7.

Bottom line: Build your machine learning system so that all parts of it (including model training, testing and serving) can be containerized.

CI/CD

A lot of data scientists and people coming from academia don’t realize how important a decent Continuous Integration and Deployment set of tools and processes is for mitigating the risks of ML systems. If you are reading this and wondering, “yeah but is CI/CD really that important?” I’d recommend checking out The DevOps Handbook by Kim et al.

In the context of ML Systems, having all aspects of your ML pipeline, including training and testing, baked into your automated testing and deployments results in much better outcomes - if you’re testing correctly! (See part 6). It can also be a huge help for creating audit logs.

Deployment Strategies

Don’t just throw your model into production! Explore the many different ways to deploy your software (this is a great long read on the subject), with “shadow mode” and “Canary” deployments being particularly useful for ML applications. In “Shadow Mode”, you capture the inputs and predictions of a new model in production without actually serving those predictions. Instead, you are free to analyze the results, with no significant consequences if a bug is detected.

As your architecture matures, look to enable gradual or “Canary” releases. Such a practice is when you can release to a small fraction of customers, rather than “all or nothing”. This requires more mature tooling, but it minimizes mistakes when they happen.

6. Testing

If you are not a software engineer, you may view tests as a “nice to have”. This is inaccurate. They are crucial. ‘Nuff said.

However, vanilla unit/integration/acceptance tests (follow this good reference to understand the different types of tests) won’t cut it for machine learning systems. In addition to those tests, it’s worth expanding the toolkit to include:

-

Differential Tests: Where you compare the average/per row predictions given by a new model vs. the predictions given by the old model on a standard test data set. You need to tweak the sensitivity of these tests depending on the model use case. These tests can be vital for detecting otherwise healthy-seeming models, for example where an outdated dataset has been used in training, or a feature has been accidentally removed from the feature selection code. These sorts of ML-specific issues would not cause traditional tests to fail. What’s worse, without effective differential tests, you might have no idea about this mistake until long after the damage is done. You don’t want to have to explain this sort of thing to a regulator.

-

Benchmark Tests: These tests compare the time taken to either train or serve predictions from your model from one version to the next. They prevent you from introducing inefficient code additions to your ML applications. Again, this is something that is hard to catch with traditional tests (although some static code analysis tools will help). If you’re working with Python, the pytest-benchmark library is worth checking out.

-

Load/Stress tests: These are not really ML-specific, but given the unusually large CPU/Memory demands of some ML applications, these sorts of tests are particularly worth performing.

All of the tests above are much easier with containerized applications, as it makes spinning up a realistic production stack trivial.

7. Deployment

There is nothing in this section that isn’t equally applicable to any non-ML system, and that is deliberate. Don’t try and reinvent the wheel with your machine learning application deployments, established practices will save you pain.

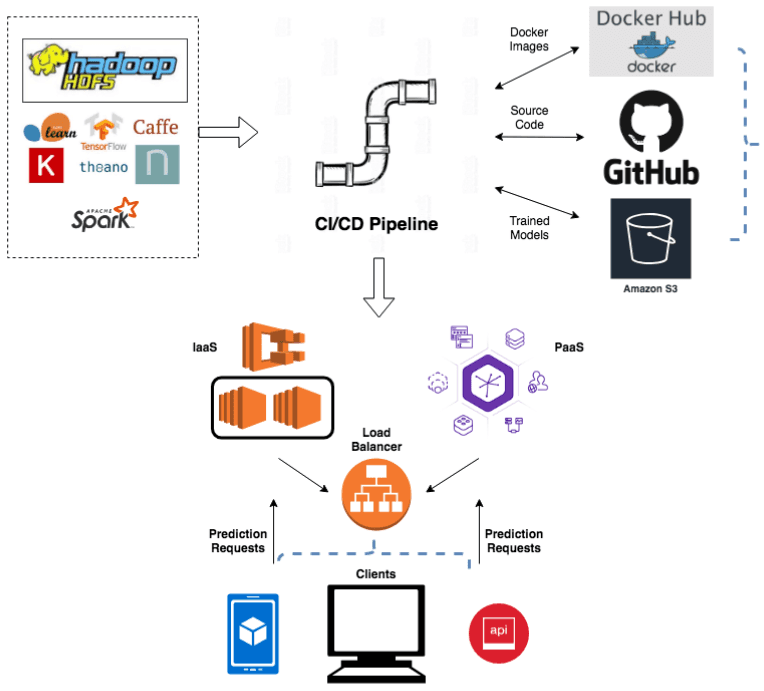

When it comes to deployments, you need to decide if you’re going to go with a Platform as a Service (PaaS) or Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). A PaaS can be great for prototyping and businesses with lower traffic. Eventually, once the business grows and/or traffic increases, you’re going to need to embrace more complexity with IaaS. There are plenty of solutions from the usual suspects (AWS, Google, Microsoft), as well as an army of niche players hoping Jeff Bezos doesn’t wipe them out one day. If you’ve never deployed anything before, I’d recommend starting with Heroku.

If your applications are containerized, deployments on most platforms/infrastructure tend to be easier. Containerization also gives you the option to use a container orchestration platform (Kubernetes is now the standard) to rapidly scale the number of containers as demand shifts.

Be sure that your deployments occur via a Continuous Deployment platform.

An example set of components involved in the whole deployment lifecycle:

8. Monitoring and Alerting

Monitoring and alerting are important considerations when deploying a machine learning system. I’ve written a dedicated post on the topic of ML monitoring. As your system grows in complexity, you are going to need monitoring capabilities and pager alerts to tell you when predictions for a particular system are outside of the expected range. Monitoring and alerting can also be related to tangential concerns, such as when training your shiny new convolutional neural network burns through your monthly AWS budget in 30 minutes. You will want dashboards which allow you to quickly check the deployed model versions running in India and China. There are many open source and paid tools to help you perform these sorts of tasks, and it doesn’t really matter which one you use, so long as you take the time to properly configure your chosen solution to give you full visibility into your system. Time and again, I’ve seen these sorts of monitoring and alerting fixes brought only after something goes wrong.

9. What Others Do

It’s indicative of the complexity of machine learning systems that many large technology companies have created their own platforms for building and deploying ML solutions. Here are some examples:

- Uber’s platform is called Michelangelo

- Facebook has FBLearner Flow

- Google has TFX

- Databricks have MLFlow

Clearly, effective building and deployment of machine learning systems is hard. Whilst it is relatively easy to pickle a model and get it behind a Flask REST API, it’s the ongoing maintenance, iterative adjustments and regulatory burden that are the real sources of difficulty.

10. The Changing Landscape

The platforms, tooling and frameworks for “doing machine learning” are rapidly evolving. A few interesting areas to watch:

- Kubeflow aims to simplify machine learning on Kubernetes. It’s still relatively new, with all the risks that entails, but it will enable smaller teams with less DevOps expertise to do complex container orchestration for machine learning tasks.

- The growth of serverless solutions, with the usual suspects weighing in (Azure Functions, Google Cloud Functions, AWS Lambda), combined with on-demand ML APIs from the same players.

- More ways to bridge the gap between the research and production environment, for example at Netflix they have invested significant effort into being able to use Jupyter notebooks for production tasks.

- More companies creating solutions focused on the issues discussed in this post - data labeling and versioning, model automated testing, validation and lifecycle management.

- Client-side machine learning with TensorFlow.js. This is still very bleeding edge, and it’s not clear to me how comfortable companies will be allowing all their model code to be readable by the competition.

- Growth of so called “real time” ML systems, where models are updated constantly as new data streams come in. This is in part helped by the established position Apache Kafka has now created, but there are interesting alternatives gaining traction such as Apache Pulsar.

In short, the whole space of machine learning deployments and lifecycle management is probably going to look quite different in a few years time. But by now, that shouldn’t really come as a surprise…